Filippo Fontanelli

I know it’s wrong but I just can’t do right. First impressions on judgment no. 238 of 2014 of the Italian Constitutional Court

Ouverture

On 22 October 2014, the Italian Constitutional Court (CC) delivered the judgment no. 238 of 2014. This ruling reignited the fire of Ferrini (a 2004 judgment of the Italian Supreme Court), which kept burning under the ashes, after the intervention of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) had seemingly put it off for good. It is only possible to appreciate the import of the CC’s judgment in perspective, as the last (or latest) act of a legal melodrama that would be entertainingly captivating if it were not real.

28 Ottobre 2014

Siragusa and the eternal recurrence. Reviving old tests to apply the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights to national measures.

On 6 March 2014, the Court delivered the order in the Siragusa case. This decision sheds new light on the old question of the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (Charter) to national measures. In particular, Siragusa challenges the efficiency of the recently minted Fransson/Texdata equivalence, and draws on the almost 20-year old precedents in Annibaldi, Maurin and Kremzow to suggest a more articulated and composite test. The case adds an episode to the disorienting jurisprudence of the Court on article 51(1) of the Charter (a thorough analysis has just been published here).

26 Maggio 2014

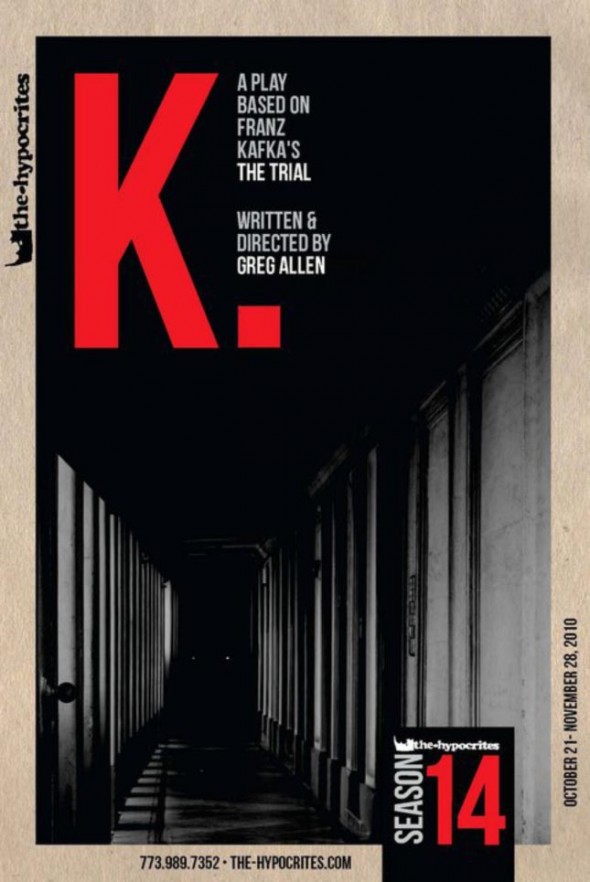

Kadi II, or the happy ending of K’s trial – Court of Justice of the European Union, 18 July 2013

On July 18, 2013, the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union (“the Court”) handed down the judgment in the so-called Kadi II dispute. With this decision, the Court dismissed the appeals brought by the Council, the Commission and the UK against the General Court’s judgment of September 30, 2010 (find here a comment, in Italian). In so doing, the Court has confirmed that Mr. Kadi’s inclusion in the list of subjects whose resources must be frozen on account of their potential relationship with Al Qaida was in breach of his fundamental rights. Therefore, the Court upheld the annulment of the Commission Regulation No 1190/2008, in the part providing for Kadi’s renewed enlisting in the blacklist found in Annex 1 to Regulation No 881/2002.

* * *

The two-level Kadi II litigation follows at the heels of the famous Kadi proceedings (also two-folded: Tribunal of First Instance, 2005; ECJ, 2010). Before turning to the reasoning of the Court in the 2013 judgment, the factual and legal scenario in which the three previous judgments took place will be sketched out briefly to provide some perspective.

In 1999 the Security Council of the United Nations passed Resolution 1267 under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. This act provided for the freezing of the assets of individuals and organisations suspected of having links with terrorist activities run by the Taliban. States can submit to the Sanctions Committee a request for inclusion of a subject in the Consolidated List, together with the relevant supporting evidence. In 2006 (see Resolution 1730) the Security Council established a ‘focal point’ to deal with delisting requests. Since 2009 (see Resolution 1904) the Office of the Ombudsperson has assisted the Sanctions Committee in dealing with delisting requests. Shortly after the 9/11 attacks, Mr Kadi, upon request of the USA, was included in the Consolidated List by the Sanctions Committee, on grounds of his suspected association with Usama bin Laden. His name was subsequently included in the EC Council Regulation implementing the UN Security Council resolution (No 467/2001, then repealed and substituted by No 881/2002, see Annex I).

Mr Kadi brought proceedings in 2001 before the (then) Tribunal of First Instance seeking annulment of these EC Regulations, in so far as he was directly concerned. He claimed violation of his right to be heard, respect for property, and effective judicial review, as well as breach of the principle of proportionality. In 2005, the TFI dismissed Mr Kadi’s claim (see judgment here). It held, in essence, that the Regulations challenged enjoyed immunity from judicial review, since they were designed to give implementation to international obligations which left no margin of discretion to the EC. The Tribunal declined to exercise its judicial review on the determinations made by the Security Council and was content to note that no breach of jus cogens had occurred, which could have possibly justified an exception to the immunity principle.

In 2008, on appeal, the Court of Justice reversed the TFI’s decision (see judgment here). The Luxembourg judges famously referred to a core of constitutional principles that buttress the rule of law within the EU and cannot be prejudiced by unconditional compliance with international obligations. Since the legality of EU acts depend on their conformity with the minimum standards of fundamental rights protection, EU judicial bodies can review them, using the jurisdictional mechanisms set in the Treaties. As to the nature of such review, the ECJ held that it must ensure ‘in principle the full review’ of EU legal acts, including those designed to implement UN Security Council’s resolutions (para. 326). In performing such review, the ECJ concluded that Mr Kadi’s rights to property and judicial protection had been breached, mainly due to the EU’s absolute failure to communicate to him any of the information upon which the listing had been decided. As a consequence, he was unable to submit his views effectively with the purpose of challenging the listing measure: he was in other words deprived of the right to defence and of effective judicial review. The ECJ thus annulled the challenged Regulation, allowing for the maintenance of its effects for three months, so as to give some time to the EU institutions to remedy the procedural wrongdoing.

Shortly after this judgment, the Sanctions Committee authorised the transmission to Mr Kadi of the narrative summary of the reasons for his listing. They are reported in full at par. 28 of the Court’s 2013 decision. In a nutshell, Mr Kadi was listed because he had founded and directed the Muwafaq Foundation, which was alleged to belong to the Al Qaida network and to support to mujahidin in Bosnia during the war in Yugoslavia. Moreover, a director of the Foundation was alleged to have regular contacts with Usama bin Laden for the purpose of providing military training to Tunisian mujahidin. Mr Kadi was also shareholder of a Bosnian bank where a terroristic plot might have been planned, as well as of other Albanian firms which allegedly funnelled money from and to extremists.

The Commission referred to these reasons to motivate the decision not to remove Mr Kadi from the list annexed to Regulation No 881/2002, and gave him the possibility to submit comments. This procedure, in the Commission’s intentions, was clearly designed to meet the procedural requirements indicated by the ECJ and therefore to obliterate the human rights deficiencies tainting Mr Kadi’s listing. In Regulation No 1190/2008, the Commission acknowledged Mr Kadi’s submissions but concluded that they could not warrant delisting.

Mr Kadi then brought new proceedings before the General Court, seeking annulment of Commission’s Regulation 1190/08. In its 2010 decision (found here), the General Court referred – not without some perplexity – to the dictum of the ECJ, which had called in 2008 for ‘in principle full review’ of all EU acts. It therefore held that the delisting procedure available before the Sanctions Committee failed to offer the minimum guarantees of judicial protection, nor had the system set up at the EU level offered any additional protection of Mr Kadi’s rights. The General Court also noted that the judicial review could not be limited to the merits of the contested measure but should necessarily extend to the evidence on which it was adopted. The kind of review advocated by the Commission, the General Court noted, would be tantamount to ‘a simulacrum’ of effective judicial review (par. 123). In the instant case, this required an examination of the information available to justify the listing, which could not be barred by reasons of secrecy or confidentiality. Ultimately, the General Court considered that the process put in place by the Commission to allow Mr Kadi to submit his views was superficial and formalistic. The main flaw of that procedure was that Mr Kadi had not been given access to the any of the information used against him, other than what was contained in the summary of reasons. As a consequence, the fundamental rights violations highlighted by the ECJ had not been healed and the General Court annulled the 2008 Regulation.

The Council, the Commission and the UK appealed the judgment of the GC. Thirteen member states intervened in support of the appellants, asking the CJEU to set aside the 2010 judgment of the General Court. The grounds of appeal can be summarised as follows: 1) the GC erred because it failed to recognise that the challenged Regulation is immune from judicial review; 2) the GC’s review of the contested Regulation was too intrusive, and should have rather been deferential; 3) the GC erred in assessing the merits of the annulment claim, failing to appreciate the counterbalancing measures that prevent a violation of Mr Kadi’s fundamental rights (such as the need for confidentiality and the procedures available to allow Mr Kadi to submit his views).

In October 2012, Mr Kadi was delisted by the Sanctions Committee, following a request for delisting channelled through the Ombudsperson. As noted in this great post, Mr Kadi did not give up on the proceedings before the Court, seeking to obtain a pilot-judgment.

The Court dismissed the first claim very swiftly, borrowing the reasoning from its own precedent in Kadi I: the EU is a legal order based on the rule of law, and protection of fundamental rights is an essential component thereof (par. 66). It follows that all EU acts must be amenable to judicial review for compliance with fundamental rights, without prejudice to the primacy of UN Security Council’s resolutions (par. 67). This brief remark represents the consecration of the dualist approach inaugurated in Kadi I: maintenance of the constitutional values of the EU prevails over the risk of incurring international responsibility for failure to comply with international obligations. When push comes to shove, the Court will strike down abhorrent EU acts, regardless of their UN imprimatur. Likewise, the Court was not particularly impressed by the argument regarding the intensity of the review: review must be full, in principle, and Art. 275(2) TFEU squarely empowers the Court to carry it out (par. 97).

The thrust of the decision concerned the merits of the claims, ie, whether Mr Kadi’s rights to judicial protection and property had been unjustifiably restricted. The Charter of Fundamental Rights lists the right to be heard, the right to have access to the file and the right to ascertain the reasons upon which a decision is taken (see Articles 41(2) and 47). Art. 52(1), on the other hands, allows for the necessary restrictions of Charter’s rights, subject to a requirement of necessity, proportionality and contribution to objectives of general interest.

Within this legal framework, the Court turned to the listing procedure, and identified the major cause for problems: whereas the EU is bound to respect fundamental rights (in all circumstances, and therefore also) when it implements Security Council’s resolutions, the Sanctions Committee is under no obligation to disclose the information used to adopt its decisions to the subjects listed or to the EU, the only exception being the summary of reasons (par. 107). All issues arise from this gulf between the duties of the EU and the lack of duties of UN bodies. In particular, the Court noted that the right to effective judicial protection under Art. 47 of the Charter requires an ascertainment that decisions affecting individuals are taken on sufficiently solid factual bases (par. 119). Hence, the review cannot stop at the logical cogency of the reasons stated in the decision, but must ascertain whether they are substantiated on the basis of reliable evidence. In the instant case, all that the Commission could rely on was the summary of reasons. The task of the Court, therefore, was to ascertain whether any one of those reasons, in the absence of further supporting information, could be sufficient to justify the listing of Mr Kadi.

Significantly, the Court did not equate the failure to disclose the evidence supporting the summary of reasons with an automatic violation of the right to defence (par. 137): the EU institutions are under no general obligations to submit this information to the Court. However, if they chose not to do so (or, like in the instant case, are simply unable to do so because the Sanctions Committee will refuse to share it), the risk of violation increases together with the summary’s vagueness. The Court did not disregard the possibility that the confidentiality of the information require its non-disclosure for security reasons, but reserved for itself the power to ascertain whether a claim of non-disclosure is founded. If secrecy is not justified, the Court will examine the lawfulness of the contested measures solely on the basis of the disclosed information (par. 127). Otherwise, a balance must be struck between the need for confidentiality and the principle of equality of arms – the Court will again be the subject entrusted with the determination of whether the balance was reached or, to the contrary, the rights of the person concerned are unduly restricted (par. 129).

The Court then criticised the General Court for dismissing wholesale the probative value of the summary of reasons for lack of detail (par. 140) and for inferring the breach of Mr Kadi’s rights from the sole fact that the information held by the Sanctions Committee were not disclosed to anyone, let alone to Mr Kadi. In fact, it is possible, in the abstract, that the summary of reasons be sufficient evidence to justify the listing, and the simple fact that more detailed information are not disclosed is not per se decisive. The Court agreed with the General Court that one of the reasons of the summary was irredeemably vague (the one regarding the unspecified Albanian firms) but found on the contrary that the other reasons were sufficiently detailed, as they referred to the identity of the persons involved and the nature of the wrongdoing alleged.

The Court then examined the other allegations contained in the summary of reasons, together with Mr Kadi’s comments and the Commission’s replies (paras. 151 to 163). It noted that, invariably, the Commission had not been able to answer Mr Kadi’s comments satisfactorily. In the face of detailed exculpatory submissions by Mr Kadi, the Commission’s failure to substantiate further the reasons for listing was tantamount to a failure to discharge the necessary burden of proof. Therefore, the contested Regulation, as previously held by the General Court, is unlawful, and the errors committed in first instance did not affect the correctness of the order of annulment (paras. 164-165).

The Court appeared to stand by its 2008 precedent, in spite of the mounting pressure by all Member States and of the obvious risk that its reasoning be used in countless similar delisting cases in the future. Far from being a decision of principle, it is nevertheless a decision based on principles: its value lies squarely in its systemic impact (beyond the instant case), as it incarnates the idea that certain fundamental rights cannot be silenced under the cover of generic security concerns.

* * *

The simple recapitulation of the court vicissitudes endured by Mr Kadi and his legal team is so dense that no further comments should be added here. Commentaries, of course, will flourish and some of them are already in the making (here an example). Readers are warmly encouraged to share their views in the comment section, below.

As a final thought, suffice it here to justify the title of the post, hinting at the striking parallel between Kadi’s saga and Mr K’s trial. Both Messrs K. faced everlasting and frustrating judicial proceedings based on allegations that were never fully communicated to them. Regardless of whether the Court’s decision is correct (let alone just in a wider sense), it is somewhat comforting to note that the rule of law in the EU is alive and kicking. An individual, suspected of connections with Al Qaida, can succeed against the aggregate hostility of the Council, the Commission and a plethora of member states, with no other weapon than the set of guarantees listed in the Charter of Fundamental Rights (an apparently unfrozen wealth also helped, at least if one reads the names featuring in his all-star legal team).

29 Luglio 2013

Anti-terror Database, the German Constitutional Court reaction to Åkerberg Fransson – From the spring/summer 2013 Solange collection: reverse consistent interpretation.

In a previous post, I maintained that the judgment in the Åkerberg Fransson case did not extend the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights beyond the familiar area derived from the doctrines of ERT and Wachauf. In that case, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) expressly defined the scope of the Charter and EU law as coterminous, therefore averting the risk that the Charter become an autonomous platform of additional EU competences. However, some commentators interpreted this judgment as a troublesome example of competence-creep sanctioned by the CJEU. Among them, in an unfortunate restaging of the post-Mangold drama, figure the judges of the German Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassugsgericht, hereinafter ‘BvG’). Their reaction did not take long to materialise: less than two months after Fransson they delivered the decision in the “Anti-terror Database” case (Judgment 1 BvR 1215/07 of 24 April 2013). This judgment is a loud signal to the CJEU, whereby the Karlsruhe tribunal made clear that it will not ratify any trend of uncontrolled expansion of the EU’s competence in human rights protection, obtained through the application of the Charter to areas remotely touched upon by EU law.

The complainant challenged the constitutionality of the German Act on Setting up a Standardised Central Counter-Terrorism Database of Police Authorities and Intelligence Services of the Federal Government and the Länder. This law regulates the exchange of information between the police and intelligence agencies and poses a threat to the right to privacy of those people whose personal information are collected and exchanged.

The BvG affirmed that the challenged provisions pursue nationally determined objectives which ‘are not determined by EU law,’ and can regard it ‘only in part.’[§§ 88-89] Accordingly, the Charter cannot apply and the CJEU cannot be the juge naturel for the human-rights review of this measure. [§ 91] However, the BvG candidly exposed all the possible links between the German measure and EU law; they are not few. The EU has legislated in the field of data protection and in particular on the limitations on the use of personal data by commercial actors; it developed a series of anti-terrorism policies that include the treatment and exchange of data relating to terrorism investigations. The “Anti-terror Database,” therefore, has direct implications that spread across the field of application of EU law.

The BvG refused to raise a preliminary question to the CJEU, invoking the acte claire doctrine of CILFIT, therefore making sure to reserve the last word on the matter for itself. Moreover, it refused to consider the application of the Charter to the Anti-terror Database, because it does not implement EU law under Art. 51(1) of the Charter. [§ 90] The strength of the link with EU law is too low to grant application of the Charter and the BvG invoked para. 22 of Annibaldi to validate this view. In that passage, the CJEU excluded the application of fundamental principles to national legislation which, despite ‘be[ing] capable of affecting indirectly the operation of an [EU norms],’ ‘pursues objectives other than those covered by [the latter].’ The choice to invoke this exemption is understandable: it is the only one available in the case-law on general principles, once the application of EU law is confirmed (which is also the reason why the BvG had to resort to the acte claire justification to escape the obligation of Art. 267 TFEU).

What is more debatable is whether this exemption applied in fact: even if the origin of the German measure is fully domestic its objectives seemingly correspond to those pursued by EU law. There is no other primary purpose of the Anti-terror Database which makes the EU ones ancillary: the measure operates ‘within the scope of EU law’ and shares its aims. In this sense, the subsequent distinguishing of Fransson is a red-herring: the Anti-terror Database is subjected to the Charter simply because the Annibaldi exemption does not apply, hence there was no need to flag the destabilizing potential of Fransson. In this sense, the BvG tried to dress its reluctance to submit the Database to the CJEU’s scrutiny as a wise act of conflict-prevention, taken ‘in the spirit of cooperative coexistence’ (literally, ‘Im Sinne eines kooperativen Miteinanders’ a formula reminiscent of that used in Honeywell, § 57: ‘wechselseitige Rücksichtnahme,’ which corresponds roughly to ‘mutual consideration,’ see this post).

In particular, the BvG noted that an expansive reading of Fransson would render it akin to an ‘obvious’ ultra vires act endangering the protection of fundamental rights in the member States, of the kind foreshadowed in the recent Lissabon Urteil and Honeywell judgments. Similar acts would force the BvG to act in civil disobedience and denounce the decision of the CJEU (as the Czech constitutional court did in 2012). Therefore the BvG specified which interpretation of Fransson might avert this risk, in an unprecedented exercise of reverse consistent interpretation (i.e., how to interpret Art. 51(1) of the Charter in conformity with the core values of the Grundgesetz). Art. 51(1) of the Charter, the BvG specified, cannot operate when the domestic measure relates to the ‘purely abstract scope of EU law’ nor when it has a ‘merely de facto’ impact on it.

Seemingly, the BvG decided to act as the champion of constitutional gatekeepers in the Union, in the immediate wake of a couple of decisions (Melloni and Fransson) whose combined effect is perceived to sanction the inexorable marginalization of constitutional tribunals in an area where they have long lost the home-field advantage: review of human rights’ compliance of domestic norms. National constitutions are sidelined when EU law applies even remotely or when domestic measures happen to fall within its scope (Fransson). In addition, State-specific constitutional guarantees stand no chance of survival when they collide with the standards set by the Charter (Melloni). It is fair to say that, even if neither decision seems to constitute the kind of ultra vires act feared by the BvG in the Honeywell judgment [§ 66], certainly the slow but irreversible application of the Charter is eroding the jurisdiction of constitutional tribunals (see above) and the scope of application of national guarantees that do not mirror EU standards. This decision served Bruxelles with a notice of warning: the terms of the peaceful entente cannot act always in favour of the EU regime, lest the BvG be ready to denounce the contract (the constitutional synallagma, see G. Martinico’s ‘The Tangled Complexity of the EU Constitutional Process, pp. 44 f) and renegotiate the well-documented status of constitutional tolerance.

3 Maggio 2013

Fransson and the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights to State measures – nothing new under the sun of Luxembourg

In case C-617/10 Fransson, the elusive matter of the application of the Charter to national measures came to the forefront once more (see this previous post that touched on the issue). The Swedish referring court asked the CJEU whether the principle of ne bis in idem (a general principle of EU law, but in any case one codified in the Charter, see Art. 50) could apply and be used to set aside certain domestic provisions. Under these norms, when a taxpayer provides false information to the authorities for the purpose of tax assessment, not only might she incur a tax surcharge, but she could also face criminal prosecution for the same misconduct. The claimant in the main proceedings argued that this scheme of penalties amounted to a violation of the principle of ne bis in idem, contained in the EU Charter (Art. 50) and the ECHR (Art. 4 of Protocol No 7), and requested the judge to set aside the Swedish provisions.

The judge, however, could not conclude with certainty whether the Charter applied in the case at stake, as it was controversial whether Swedish dual system of tax penalties had an impact on the ‘implement[ation of] Union law,’ or in any case fell, ratione materiae, within the scope of application of EU law, as required by Art. 51(1) of the Charter. Some ‘presence’ of EU law was traceable in the form of Directive 2006/112. Art. 273 of the Directive entitles States to ‘impose other obligations which they deem necessary to ensure the correct collection of VAT and to prevent evasion.’ Would that be enough to consider the Swedish bifurcated system of imposing tax surcharges and prosecuting tax offences as falling within the purview of EU law (for the purpose of the application of the Charter)?

Advocate General Cruz Villalón conceded that the case-law has not yet clarified the specific import of Art. 51(1) of the Charter, and daringly suggested a principled approach to interpret it, which would help clarify its construction also pro futuro. He took cues from the rationale behind the possibility that State action be reviewed for conformity with EU principles. He saw in this possibility an exception to the rule that it is for member states to review acts of their public authorities. The controlling criterion, the AG said, is the existence of a ‘specific interest’ of the Union to centralize the human-rights review of measures governing certain matters. Not every exercise of power whose ultimate origin is located in EU law needs to be informed by the EU-conception of a fundamental right: it must be possible to isolate those situations in which ‘the Union’s interest in leaving its mark … should take priority over that of each of the Member States.’ [41] Only in such cases, where the Union has an interest to review the lawfulness of the exercise of State public authority, is it possible to subject state measure to the provisions of the Charter (and to EU general principles at large).

As regards the instant case, the AG ultimately argued that the link between the EU legislation and the Swedish measures appeared to be too tenuous to substantiate this interest. The AG distinguished between the case in which national legislation is ‘based directly on Union law’ and the hypothesis that it is ‘used to secure objectives laid down in Union law’ [60], referring to the difference between causa and occasio. In the main proceedings, the commencement of criminal prosecution – the only element that could fall within the reach of the ne bis in idem rule – was simply an inessential circumstance, a Member-specific normative contingency incapable of affecting the EU competence on VAT collection.

The CJEU thought otherwise. It ignored the AG’s invitation to investigate the EU’s specific interest and to mind the gap between causæ and occasiones, and stuck to the classic (and sibylline) interpretation of Art. 51(1) of the Charter, whereby domestic acts must comply with EU law when they fall within the scope thereof (see Annibaldi, [21-23]). In short, the CJEU recalled all provisions of EU law that require member states to ensure the collection of VAT and to prevent VAT evasion and noted that any shortcoming in the domestic collection of VAT affects the EU budget, in so far as the latter depends directly on the former [26]. Moreover, since member states are obliged to counter all wrongdoing affecting the EU’s financial interests, under Art. 325 TFEU, the Court concluded resolutely that:

tax penalties and criminal proceedings for tax evasion, such as those to which the defendant in the main proceedings has been or is subject because the information concerning VAT that was provided was false, constitute implementation of Articles 2, 250(1) and 273 of Directive 2006/112 (previously Articles 2 and 22 of the Sixth Directive) and of Article 325 TFEU and, therefore, of European Union law, for the purposes of Article 51(1) of the Charter [28].

Even if the Swedish legislation at bar was not designed to transpose Directive 2006/112, its application ‘is designed to penalise the infringement of that directive’ and, therefore, ‘intend[s]’ to implement the Treaty-derived obligation to safeguard the financial interests of the EU through the imposition of effective penalties. As a result, the Charter applied, and the CJEU just made a point to quote the Melloni decision, published on the very same day, to remind Sweden that it was still possible to apply national standards, provided that the level of protection required by the Charter was complied with, lest the ‘primacy, unity and effectiveness’ of EU law be compromised.

A couple of comments are in order. First, the CJEU should be excused for the generous use of words like ‘designed’ and ‘intended’ to describe the link between the application of national measures and the implementation of EU obligations. Not only are the relevant provisions of Swedish laws on tax offences and tax assessments referred to taxes in general, and do not contain an express reference to VAT, but a factual remark might suffice to appreciate how the ideas of design and intention are ill-suited. The relevant Swedish provisions, quoted in the judgment, were adopted in 1971 and 1990. Since Sweden joined the EU only in 1995, it is hard to believe that the Swedish legislator designed them with the intention to implement obligations that did not bind Sweden at the time. A semantic shift from the area of intentions and aims to that of effects and results would certainly be appropriate (a well-rehearsed topic of international trade law, see here, for example). Moreover, it would certify that the focus idea of implementation of Art. 51(1) of the Charter is not the subjective element of state measures but their objective contribution to the implementation of EU law. This shift would better explain situations like the Swedish one, in which national measures happen, more or less unintentionally, to govern matters covered by EU law, and are therefore capable of hindering or promoting the attainment of the objectives set therein.

Second, a look at the EU provisions ‘implemented’ might provide further insight on the CJEU’s take on Art. 51(1) of the Charter. Of the provisions of Directive 2006/112 that were mentioned, one simply lists the transactions subject to VAT (Art. 2), one simply requires that all taxable persons submit their VAT return (Art. 250(1)), and one empowers member states to impose additional obligations to ensure the correct collection of VAT and prevent evasion (Art. 273). Of the three, only Art. 273 seemingly bears a link with the Swedish system of sanctions for tax evaders, whereas the other two are only useful to identify who is under the obligation to pay VAT, for which transactions, and through which assessment procedure. The CJEU, it is argued, should have kept Art. 2 and Art. 250(1) of the Directive out of the discussion on the relationship between the Swedish scheme of sanctions and EU law. To be sure, these provisions clarify the reach of the obligation to whose enforcement Art. 273 refers. However, unlike the latter provision, Articles 2 and Art. 250(1) of the Directive are hardly implemented by the Swedish measures. As to Art. 325 of the TFEU, instead, it is arguably uncontroversial that the national provisions sanctioning tax evasion, in so far as they also apply to VAT evasion, act as a deterrent implementing EU-imposed obligation to ‘counter fraud and any other illegal activities affecting the financial interests of the Union.’

Although the CJEU missed the opportunity to set the record straight and devise a brand new test for the application of Art. 51(1) of the Charter, as suggested by the AG, at least it gave helpful guidance to the national judge, unlike in previous cases like Kamberaj and Scattolon. Yet the mixture, in the decisive paragraphs, of EU provisions that are arguably implemented by the national measures and others that are not might prove confusing, and the impression is that some of them would not have justified the application of the Charter under Art. 51(1) thereof, if considered separately.

Parsing one judgment is not the ideal starting point to venture into a far-reaching analysis of how Art. 51(1) of the Charter might be construed in the future. If anything, one should keep an eye on the Court’s practice of considering within the scope of EU law those national measures that, simply, contribute to the implementation of an EU obligation without being primarily designed to transpose it. There might be cases where the link might prove too thin to matter, and the Court may then regret having discarded Cruz Villalón’s suggestion to exercise value-judgment, in order to make that call with more confidence.

1 Marzo 2013

The UK Supreme Court ruling on privacy, proportionality and scalpers’ right to anonymity.

Tickets for major sport events are scarce and sought-after. Scarcity and passion drive their price up, at least the price that someone is willing to pay in spite of their face value. This price differential is the backbone of the secondary market, in which trade actors better known as scalpers provide their questionable – and yet often providential – service. Even for sold-out events, of one thing we can be certain, if we have heard of Ronald Coase (see here): regardless of who happen to buy the tickets from the issuers in the first place, these tickets will belong in the end to those who are ready to pay the highest amount. As Scott Simon puts it, ‘[w]ithout obstacles to this process, a series of bargains will be struck until all tickets are in the hands of the highest-valuing users’. Along with scalpers, it follows, other subjects are in the business of facilitating the operation of this market, namely those who remove the ‘obstacle to this process,’ ie transaction costs.

Among them is Viagogo, ‘the ticket marketplace,’ a company providing an online platform for individuals to exchange and sell tickets. The price of tickets on offer on Viagogo, ça va sans dire, follows closely the laws of supply and demand, and prices much above face value are routinely asked and paid for. When the organizers deliberately issue under-priced tickets or set a capped price, for instance to encourage purchase by low-income customers, or enhance the popularity of one sport, the secondary market nullifies the effect of these subsidy-like policies. Notably, resellers are able to speculate, and monetize the value-surplus inherent in the ticket purchased at face-value. It is no surprise, therefore, that primary sellers are typically against the very existence of an uncontrolled secondary market, which frustrates customer-building strategies and, more generally, enervates legions of average customers, who are not happy or ready to pay a mark-up for tickets that at times remained on sale for just minutes.

The Rugby Football Union (RFU) is the body responsible for issuing tickets for rugby matches at the Twickenham Stadium. RFU’s sale conditions stipulate that tickets are void, for breach of contract, if resold above face value. Monitoring private transactions, however, is a Sisyphean task, and RFU’s attention focused on overt and massive reselling practices, like those carried out through Viagogo.

In an attempt to monitor and fight illicit reselling, the RFU sought and obtained from the UK High Court an order requiring Viagogo to disclose the identity of the users engaging anonymously in the sale of over-priced rugby tickets. Viagogo appealed the court order and invoked inter alia the European Charter of Fundamental Rights, arguing that the ordered disclosure represented a disproportionate interference with the protection of personal data of the persons concerned, in breach of Art. 8 of the Charter. In the appeal decision, the Court of Appeal rejected this argument, declaring that RFU had no alternative means of monitoring illicit conduct, and therefore the disclosure was a proportionate measure through which RFU sought legitimately to vindicate its contractual rights.

The Supreme Court (UK SC), seised of a challenge of the appeal judgment, handed down its decision, in the person of Lord Kerr, on 21 November 2012. Two points of the decision will be explored here: the application of the Charter to the specific situation, and the proportionality assessment carried out by the UK SC.

As for the application of the Charter, the UK SC had to pass through the bottleneck of Art. 51(1): the Charter applies to Member States only when they implement EU law. The wording is vague enough to allow for everlasting speculation as to the exact meaning of this provision. Suffice it to say that there are at least two schools of thought on what implementation means under Art. 51(1) of the Charter, and both take cuse from the case-law on general principles, which also apply to State measures only when these implement EU law.

The first school follows closely the case-law of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU), which has clarified over time that the concept of implementation is such that Member States are bound by general principles when they i) implement EU law directly (Wachauf), but also when they ii) adopt measures in derogation of EU commitments (ERT). Said derogation might be justified by virtue of an express specific exception (like those listed in Art. 36 TFEU, or those envisaged in a Directive or a Regulation, see the recent NS case), a general one (Familiapress; Rutili), or a mandatory requirement (Cassis de Dijon).

A second school notices that the ERT+Wachauf test cannot cover many State measures that have nevertheless some link with EU law, or at least fall within the scope of EU competences ratione materiae. Therefore, many authors have advanced alternative rationales for the ‘implementation’ test, according to which EU general principles could also apply to at least some of these measures. One of the most innovative suggestions came from Advocate General (AG) Sharpston in Zambrano, who suggested to apply general principles to all State measures falling within the scope of EU competences (whether or not the Union had enacted any legislative act on the regulated matter). AG Cruz Villalòn, in the pending Fransson case, has proposed that Art. 51(1) should be applied with a grain of salt: regardless of the ERT+Wachauf test, the Charter applies (and so do general principles) when the Union has a ‘specific interest’ to impose on States its centralized conception of a fundamental right, by reason of the principal-agent relationship between the Union, on one hand, and Member States implementing Union law, on the other.

The UK Supreme Court, in the case at hand, seemed to espouse without hesitation the latter, ‘expansionary,’ view. In gauging whether the order of disclosure could be reviewed against Art. 8 of the Charter, it simply recalled a recent precedent of the High Court, on the point of the interpretation of Art. 51(1) of the Charter:

[28] … the rubric, ‘implementing EU law’ is to be interpreted broadly and, in effect, means [that the Charter applies] whenever a member state is acting ‘within the material scope of EU law’.

The UK SC did not elaborate on the reasons supporting this broad interpretation, which in any case yielded an uncontroversial result, since the High Court’s order concerned the disclosure of ‘personal data,’ a concept defined (better, a matter regulated) by the Data Protection Directive (see [32]). Therefore, it is fair to observe that, even endorsing a narrow interpretation of Art. 51(1) of the Charter, the conclusion is the same: national judges issuing disclosure orders must abide by the Charter.

The direct application of Art. 8 of the Charter, however, does not automatically outlaw all limitations to the absolute protection of personal data. Art. 8 itself (second paragraph) envisages the possibility to process personal data ‘on the basis of ... other legitimate basis laid down by law [as opposed to the consent of the persons affected]’. Moreover, Art. 52(1) of the Charter sets out the possibility to justify interferences with a Charter right, on condition that they be ‘provided by law,’ respectful of the essence of the right, and ‘subject to the principle of proportionality,’ which includes an appraisal of necessity.

The recent CJEU’s decision in C-461/10 Bonnier, which concerned a similar set of facts (disclosure of the identity of internet users suspected of infringing copyrights through downloading pirated audio books), provided some guidance as to which balance should be struck by national authorities:

[60] ... [national] legislation must be regarded as likely, in principle, to ensure a fair balance between the protection of intellectual property rights enjoyed by copyright holders and the protection of personal data enjoyed by internet subscribers or users.

Lord Kerr rejected the idea that the case-by-case analysis of proportionality would implicate by necessity a separate evaluation of each user’s relationship with Viagogo, and somehow trump more general considerations. On the contrary, she recognized RFU’s primary interest to have access to the sought information, and firmly founded thereon the proportionality analysis:

[40] ... The ability to demonstrate that those who contemplate such sale or purchase can be detected is a perfectly legitimate aspiration justifying the disclosure of the information sought. There is no coherent or rational reason that it should not feature in any assessment of the proportionality of the granting of the order.

The UK SC decision also took pains to distinguish the case at bar from the Goldeneye domestic precedent, where at stake was an order of disclosure of the personal information of internet customers alleged to have used peer-to-peer services to download and share pornographic material. In that occasion, the disclosure order was found to be disproportionate, due to the uncertainty regarding the actual conduct of the targeted users, the sensitive and embarrassing nature of the accusation, and the unfair and oppressive pressure that a legal claim would exert on possibly innocent users, had the order been issued.

Since none of these elements were at stake in the RFU v Viagogo dispute, the Supreme Court held that an ‘intense focus’ on the individual rights affected would not automatically lead to the conclusion that all disclosure orders are disproportionate. To the contrary, even if there might be cases where the protection of personal information overrides the need to obtain data for the purpose of an investigation, in the present case ‘the impact that can reasonably be apprehended on the individuals whose personal data are sought is simply not of the type that could possibly offset the interests of the RFU in obtaining that information’ [46].

The outcome of the balancing exercise is encapsulated in the following paragraph of the UK SC’s reasoning:

[45] ... The entirely worthy motive of the RFU in seeking to maintain the price of tickets at a reasonable level not only promotes the sport of rugby, it is in the interests of all those members of the public who wish to avail of the chance to attend international matches. The only possible outcome of the weighing exercise in this case, in my view, is in favour of the grant of the order sought.

14 Dicembre 2012

State Immunity for International Crimes: the Cassazione’s Solitary Breakaway Has Come to an End (judgment 32139/2012).

In August, the First Criminal section of the Cassazione, the Italian Supreme Court (ISC), annulled (without re-trial) a decision of 2011, whereby the Military Court of Appeal had condemned Germany to pay reparation to the Italian victims of some Nazi officers, who had been found guilty of war crimes perpetrated in Italy during the ending phase of World War II. The challenge before the ISC was brought by the German State against the tort-related section of the dispositif, and did not touch upon the criminal conviction of the defendants.

In this judgment, the Italian judges had to perform a forced (and awkward) turnabout on the issue of State immunity from civil foreign jurisdiction in the case of crimes against humanity, in the wake of the International Court of Justice (ICJ)’s judgment of February 2012. Indeed, earlier the same year, the ICJ had upheld Germany’s claim that Italy had breached the international custom providing States with immunity from foreign civil jurisdiction for acts committed in the exercise of sovereign prerogatives (acta jure imperii). Indeed, Italian courts had since 2004 started to award damages to Italian plaintiffs suing Germany for WWII-related crimes, and had dismissed Germany’s invocations of State immunity, based on a long-standing rule of customary law.

The ungrateful task of the ISC was to implement the ICJ’s dictum and to put an end to the unsuccessful campaign launched by the Cassazione itself, aiming at the creation/recognition of an exception to the general principle of State immunity. This doctrine was first heralded in the Ferrini judgment (5044/2004), it was later confirmed in the 2008 orders (see e.g. order 14201/2008 Mantelli) and it was generally accepted and applied by several courts of first instance and appeal, up until very recently.

Italy’s position in The Hague replicated the reasons provided by the ISC in the Ferrini case-law: although there certainly is a custom that confers upon States immunity from the civil jurisdiction of other States, especially if acts jure imperii are in question, there also are rules of higher status prohibiting the commission of international crimes. The effective implementation of these higher rules cannot be frustrated by the rules of immunity, especially when the conduct examined has taken place in the State of the forum.

A similar argument had been used by the Military Court of Appeal in the judgment later challenged before the ISC. It had referred to the evolutionary status of international customs and to the necessity to strike a balance between the purpose of State immunity (a safeguard for State sovereignty) and the paramount interest to indemnify the victims of the most heinous violations of human rights. Somewhat apart from the hierarchical argument (a jus cogens prohibition must trump a rule of custom), the Military Court of Appeal also declared that a new custom had indeed solidified, which was capable of derogating from the general one of State immunity. As a consequence, since German international crimes in Italy in 1944 were not committed on the initiative of single commanders but in the execution of a centralised plan, Germany was liable for damages.

After perusing the ICJ’s decision, the judges of Piazza Cavour felt the need to recapitulate the phases of the legal vicissitude described above, also to justify before the eyes of the plaintiffs the spectacular revirement they were about to include in the operative part of the decision.

The ISC took note of the main point of the ICJ’s reasoning that led to the rejection of Italy’s position: the jus cogens rank of the material norms prohibiting international crimes does not affect the rules on State immunity, which are of procedural nature and apply regardless of the gravity of the conduct. In other words, the peremptory character of the rules of behavior cannot trump the principles of State immunity, despite of their concededly lower rank. This is because there is no conflict between them in the first place: stating the contrary would be tantamount to ignore “the distinction that must be drawn between the substantive primary rule and the secondary rules that come into play once a violation has occurred” (para. 120 of the ICJ’s decision).

The ISC seised the occasion to question the correctness of such distinction, stating that

Appare[…] indebitamente riduttivo confinare la categoria dello jus cogens alla sua sola protata sostanziale, ignorando che la sua effettività concreta si misura proprio alla stregua delle conseguenza giuridiche che derivano dalla violazione delle norme imperative. [It appears unduly restrictive to confine jus cogens rules within their substantive scope. Such operation would disregard the fact that their practical efficiency is depending precisely on the legal consequences attached to the violation of peremptory norms.]

The Italian judges, in addition, noted that this distinction ends up promoting impunity and attracting crimes against humanity in the category of acts jure imperii, providing them with undeserved protection. This notwithstanding, the ISC acknowledged the undisputed authoritativeness of the ICJ’s decision, and the isolation of its own position in Europe. It took cognisance that the rationale of State immunity is to preserve sovereignty, and that – as of now – no act whatsoever can be considered serious enough to put this preservation into doubt.

Before admitting defeat, the ISC also took the chance to provide a “friendlier” reading of the ICJ’s judgment. According to this interpretation, the ICJ itself, far from disavowing the convincingness of the principles declared in the 2004 and 2008 decisions of the ISC, limited itself to register the lack of agreement thereon, and acknowledged that the ISC was legitimately bringing a contribution to “to the emergence of a rule shaping the immunity of the foreign State” in international law. The Italian decisions were therefore seen as an attempt to bring about a change in the law, which was “inspired by the principles of legal civilization”. However, the lack of consensus surrounding the Italian position could only lead to the discontinuation of the case-law it had generated.

As for the impact of the ICJ’s decision on the proceedings at hand, the ISC noted that Italy had incurred international responsibility for the acts of its judiciary, and had been ordered to restore the status quo antea, regardless of the means chosen to that aim, and irrespective of the finality of the domestic judgments already delivered.

The Court, with a slight and involuntary comic effect, declared that it had no direct obligation to follow the ICJ’s decision, but it would agree to do so spontaneously, not to aggravate Italy’s position at the international level, and to issue a judgment “reflecting the current status of international law”. It also conceded that it would not be a problem for Italy to implement the ICJ’s decision through the adoption of a statute. It had been argued that such statute might be unconstitutional ab origine, because it would be at variance with the international custom limiting State immunity from civil jurisdiction in the case of crimes against humanity – and international customs enjoy a quasi-constitutional rank in the domestic order (under Art. 10 of the Constitution). However, since it had been conclusively clarified that such international custom, in fact, does not (yet?) exist, the question of constitutionality could not arise in the first place.

The ISC, net of all the dicta aimed at explaining why it still believed to be sort-of-right, has displayed a remarkable degree of deference to the authority of the ICJ, on an issue of considerable political weight. In so doing, it had to swallow its pride and grant immunity to Germany, but the result is uplifting: Italy is a good citizen of the international community, and its State organs are aware of the obligations it has entered in. Far from creating a schizophrenic situation like those of the Avena and LaGrand cases (if you don’t remember the details, I recommend this article), the Italian judiciary acted responsibly and spared Italy from further troubles at the international level.

11 Ottobre 2012

Of shrimps and planes or how the CJEU justifies unilateral environmental measures with extra-territorial effects.

On December 21, 2011, the Court of Justice of the European Union (the Court) handed down the preliminary ruling in case C-366/10, on the request of the High Court of Justice of England and Wales. The preliminary questions aimed at assessing whether EU Directive 2008/101 was valid, in light of the international obligations of the European Union (EU), in the part imposing environmental measures on flights that are carried out, at least in part, outside the EU airspace. The Court ultimately confirmed the validity of the Directive.

In this decision, the Court took the chance to elaborate on the relationship between the law of the EU and international norms, both of conventional and customary nature. In this post, I will summarize the background of the case and the legal reasoning of the Court. Whereas I will try to provide a comprehensive account of the Court’s decision, I will limit my analysis to a specific issue – the understanding of extraterritorial jurisdiction. For further and wider comments and reflections, see this and this recent posts.

30 Aprile 2012

G.Martinico, Lo spirito polemico del diritto europeo Studio sulle ambizioni costituzionali dell'Unione, Aracne, Roma, 2011

Questo libro è il risultato di una serie di lezioni e conferenze tenute dall’Autore, attualmente García Pelayo Fellow presso il Centro de Estudios Politicos y Constitucionales (CEPC) di Madrid, in varie universitá e centri di ricerca europei (Spagna, Italia, Regno Unito, Olanda).

Questo non deve però far pensare ad un insieme di saggi indipendenti; al contrario, si tratta di un lavoro coerente e monografico, dedicato a quelle che Martinico chiama le ultime stagioni della “mega-constitutonal politics” europea (con questa espressione, l’Autore richiama i lavori di Peter Russell sull’odissea costituzionale canadese, cfr. P.H. Russell, Constitutional Odyssey: Can Canadians Become a Sovereign People?, Toronto, 1992).

23 Febbraio 2012

Why arbitration is a form of international justice (and why it is desirable that off-side calls are not reviewed by ordinary judges)

Vox Populi, vox dei?

In the Great Hall of Justice, a large painting hangs over the entrance through which Judges of the International Court of Justice make their way to the bench. Two jurisconsults, standing on a rock platform, are depicted in the midst of a debate before an arbiter, whereas a woman stands below the rock. Two knights in armor, presumably convened with some animus pugnandi, are showed parting ways, after the providential intervention of the woman, a personification of Peace itself.

This 1914 painting by Albert Besnard is commonly known under the title “Peace by justice” as, in fact, it shows how the resolution of a dispute through legal arguments prevented it from turning into a violent conflict, fought with swords.

Few know that the canvas originally bared a different title, as documented in a New York Times article of 3 October 1915, and in a preparatory sketch now kept at the archives of the Musée d’Orsay. It was called “peace by arbitrament”, and the painter, presumably drawing from a legal dictionary shaped only by popular culture and reminiscences of King Solomon, considered normal to define the administration of peace through legal reasoning an exercise of arbitration, rather than adjudication.

20 Dicembre 2011